In most “buyback-and-burn” token models, a network generates income in one currency token and uses the proceeds to buy-back and “burn” its own native token. The intent is to grow token value by reducing its supply as income grows. Buybacks tend to accomplish that goal, but burning affects currency and capital assets in different ways. When it comes to money, reducing the supply can increase the unit value of currency. But when it comes to capital assets like governance tokens, issuance is key to capitalization and burning can get in the way of growing fundamental value.

First, we’ll establish a test for whether a token is currency or capital. Then, we’ll study the components of buyback-and-burn and consider their consequences. Finally, we’ll sketch an alternative token model, buyback-and-make, which keeps the benefits of buybacks without the drawbacks of burning capital.

Currency and Capital Tokens

An asset is Currency when its value comes from exchange: when it’s spent to consume goods or services, like the U.S. dollar. ETH, for example, serves as currency because you spend it to consume Ethereum services and also to buy other assets. On the other hand, an asset is Capital when its value comes from governance or equity participation in a pool of resources. For example, company shares are basically voting instruments that govern the distribution of power and profits.

When a network generates income in one currency and re-distributes the value to its token holders in any way, we know it’s a capital asset because its fundamental value comes from those flows. MKR and ZRX are good examples: both networks generate income in ETH and redistribute the value to their (governance) token holders. Maker does it with a buy-and-burn model, while 0x re-distributes the ETH proportionally to those who stake ZRX and market-make on the network. But both tokens are capital assets that derive their value from currency flows.

(An asset can be both currency and capital – see Cryptonetwork Governance as Capital. In the transition to proof-of-stake, ETH 2.0 will transform into a currency-and-capital asset.)

How Buybacks Work

With these distinctions in mind, let’s turn to buybacks. In the public equities world, buybacks are a popular way for large companies to boost their stock price by buying their own shares in the market. Equity buybacks work by increasing the outstanding shareholders’ participation in the capital of the organization. However, bought-back shares are not automatically destroyed. By default, they continue to be held by the company as treasury shares. Unlike outstanding shares, treasury shares can’t vote or participate in the economics of the organization. Both are circular acts: there’s no sense in distributing profits to yourself, and you can’t buy what you already own.

By reducing the number of outstanding shares, buybacks improve certain valuation ratios (e.g. earnings per share, etc.) for all remaining outstanding stakeholders in the market. This justifies paying a higher price per share. But actually destroying treasury stock after a buyback is not economically useful. The buyback alone does all the work because what affects the price is how many shares participate, not how many exist – and treasury shares don’t participate.

From a governance standpoint, burning would indeed guarantee that those particular shares are never re-issued. But the people with the power to burn treasury stock are often the same people with the power to issue new units anyways. Maker, for example, burns MKR as it earns income, but can issue new MKR in case of a solvency emergency (which happened in March 2020). What ultimately controls token supply is the governance protocol and the social contract among stakeholders, so burning doesn’t actually guarantee protection against dilution.

The key point is that removing capital units from circulation works by improving participation ratios for outstanding stakeholders, not inherently because the asset is made “scarcer”, and not necessarily because the total value of the equity increased. Reducing the number of shares may boost the price, but it doesn’t change the overall value of the system. It’s the same for capital tokens in cryptonetworks: buybacks do have a positive influence on price, but burning doesn’t create new value, it only redistributes current value among a smaller group of people. There’s a reason why companies that do a lot of buybacks are associated with low growth.

Issuance, Capitalization, and Growth

Much of cryptocurrency culture associates the idea of “inflation” with an erosion of value. This can be true in the world of money. But note that the terms inflation and deflation are monetary concepts that don’t really translate to the world of capital, where issuance of participation shares is key to capitalizing the equity of a system. Issuance is the cheapest way to acquire capital for growth. In startups, for example, it’s how founders gather human and financial capital (talent and money) at a lower cost.

Issuance of capital shares how you acquire the resources needed to scale. It works the same way for more decentralized systems like DAOs and protocols. We know tokens can be issued to compensate the various participants in a cryptonetwork who contribute different kinds of capital: to producers for their work, to users for their continued business, and to investors for their capital and liquidity. In all cases, issuance helps grow fundamental value by growing the capital of the system, which then turns into a greater token price.

This is why tools like mining, proof-of-stake, and liquidity rewards can work so well. The effects are clear in the new world of liquidity mining in DeFi: protocols that reward users with tokens in exchange for capitalizing the system by providing liquidity (e.g. Compound, Balancer) grow at a much faster rate than those without such incentives for capital (e.g. Maker, Uniswap – until just now). But the basic concept, of course, goes back to Bitcoin itself – and even further back to the invention of joint-stock companies as shared organizations. Buying growth with dilution is a good deal whenever the value of the equity grows faster than the issuance rate. And as the value of the equity grows, it costs less and less dilution to acquire more capital.

It’s not that you can’t grow without issuance, but without any new issuance, there isn’t as much of an incentive to continuously capitalize the system. As a token holder, you’re more likely to increase your contribution over time if there’s some dilution than if there’s none. With burning the incentive is worse, because you’re increasing the participation of token holders without requiring them to increase their investment. And whenever the price of the token does not immediately grow at the same rate as the burn (which is most of the time) burning actually decreases the overall market cap of the network.

Reducing the supply of shares or tokens over time can discourage capitalization just like deflationary currencies discourage consumption. And if the rate of burning ever exceeds the rate of fundamental growth, you risk decapitalizing the system by over-concentrating ownership at the expense of liquidity and long-term value. There’s far more upside to smart issuance than there is in clutching to scarcity. For example, you can reissue treasury assets to continuously incentivize productive capital, resell them to raise financial capital, or even use them as collateral for credit. We have to get over the idea that increasing scarcity automatically means more value. So instead of burning, let’s think about more creative ways to recycle that capital.

Buyback and Make

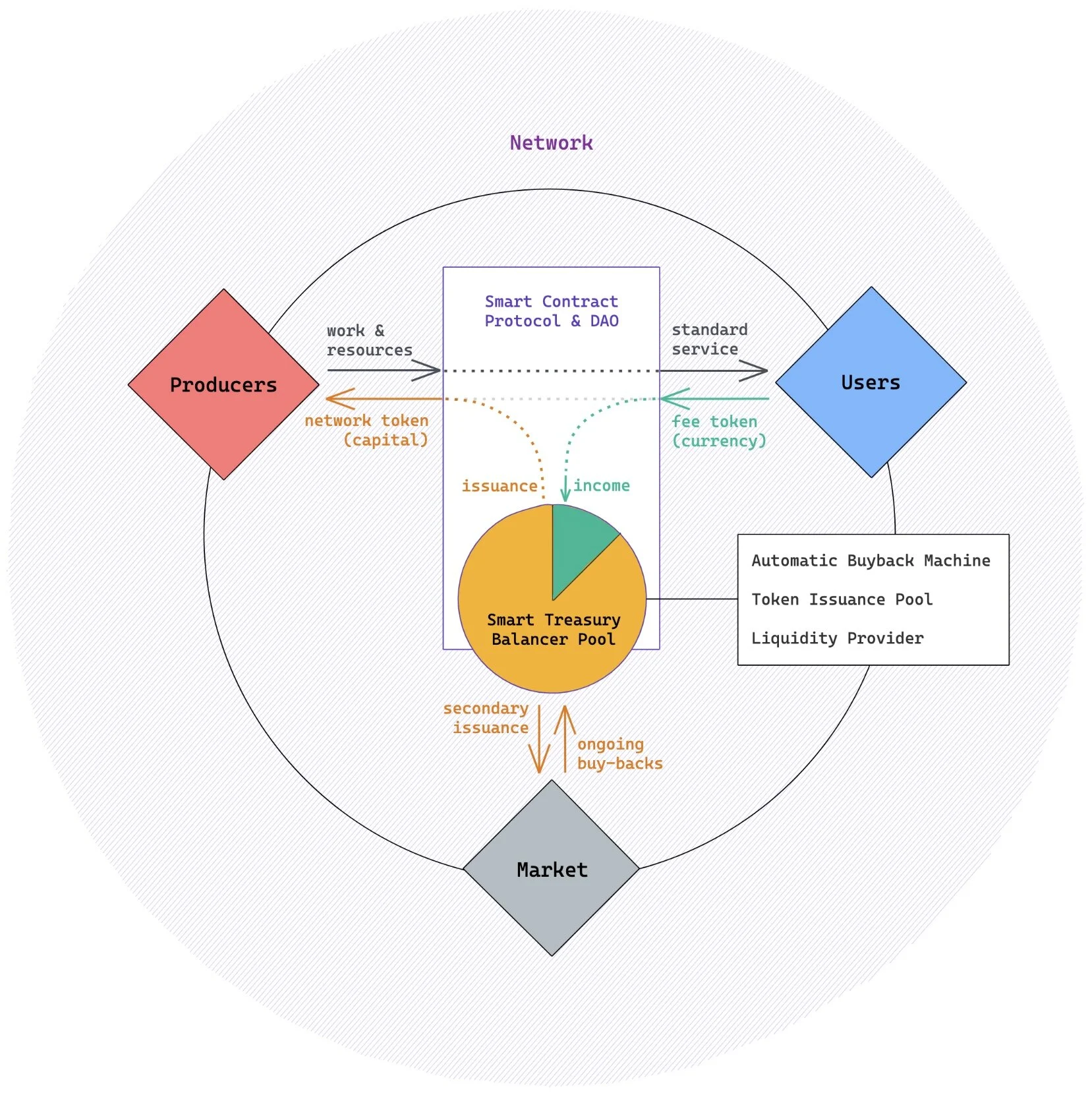

To summarize our points, buybacks are a fine way to socialize profits to capital-token holders, but burning limits the network’s ability to reinvest in itself. Buyback and Make is an alternative proposal that uses an automated market maker to keep the financial benefits of buybacks and issuance *without* the drawbacks of burning and without perpetually increasing token supply. We can do this with a protocol treasury implemented as a network-owned Balancer “smart pool” that serves as an automatic buyback machine, token issuance pool, and liquidity provider.

Buyback and Make

It’s a similar setup as the cryptoeconomic circle. The Protocol/DAO smart contracts coordinate production and regulate the exchange of productive and financial capital between producers and consumers. Producers commit work and resources (productive capital) to the network in exchange for capital tokens, subject to issuance protocol. Users consume and pay for the network’s service by spending a determined currency or fee-token. We add a Smart Treasury implemented as a Balancer pool controlled by the Protocol/DAO contracts. From now on, let’s say our Network generates income in ETH, and our token is called TKN.

Balancer is a programmable liquidity protocol and decentralized exchange. To start, it allows you to create an indexed basket of up to 8 tokens. You can choose the index based on your requirements, but for our example lets make it 10% ETH (our currency token) and 90% TKN (our capital token). We also configure the pool such that only the controller (i.e. the protocol) can add and remove liquidity from the pool, and let’s also say we minted a total maximum supply of 10,000,000 TKN and deposited them into the pool along with some ETH. Our new Balancer Network Treasury pool can do many things:

1. Automatic Buyback Machine. By depositing all (or a portion) of the ETH income generated into the pool. Whenever the value of the ETH in the Network Treasury exceeds the 10% index, our Balancer pool will automatically seek to regain balance by selling the excess ETH for TKN in the open market until the 90/10 index is restored. Because the only other token in our pool is TKN, the only way to restore balance is by buying TKN from the market (or adding new TKN to the pool). If there are no sellers, the pool responds with a higher TKN price.

Because our pool is owned by the network, this process is equivalent to a buyback – and it has the same positive effect on price. As income flows into the network and makes it to the Smart Treasury, buybacks happen in real-time and are automatically managed by the Balancer protocol. This is a lot more efficient, not only because it saves core developers from maintaining complex buy-and-burn code, but it also removes the need for special “keeper” bots and incentives to provide the liquidity needed for buy-and-burn operations. Existing arbitrageurs in the Balancer market provide this service for free in real-time, drastically simplifying the protocol.

2. Token Issuance Pool. Protocols with issuance incentives either issue new tokens as capital comes into the network or mint a certain amount of tokens in a single event and distribute them according to an issuance schedule. Our model uses the pre-mint method (although nothing prevents a hybrid approach) and deposits the number of tokens destined for distribution in the Smart Treasury from the beginning. Because only the protocol’s contracts can add and remove liquidity from the pool, the network can source the TKN it needs for incentives simply by withdrawing them from the Smart Treasury. Just like any other method, the network’s issuance model can be executed by a smart contract.

Bonus: The reverse of the buyback operation allows the Smart Treasury to act as an automatic capitalization machine. Just like adding ETH (or any fee-token) to the pool triggers an automatic buyback, withdrawing currency has the same economic effect as issuing TKN from the Treasury and selling it for currency. This feature can be used to raise money for expenses continuously, as necessary. For example, a DAO could withdraw currency to pay for development costs, or a protocol could use the fee-token balance in the treasury as an “insurance fund” backed by the network’s token. This is useful for protocols that use their tokens as last-resort insurance (like Maker’s MKR), but again without the need for special keepers or auctions to make sure tokens are minted and sold at the right market price – Balancer includes those guarantees for free.

3. Liquidity Provider. Finally, our Smart Treasury also acts as a liquidity provider. Because the assets in our Balancer pool are also available through its decentralized exchange, it means buyers and sellers of TKN have guaranteed liquidity because they can always trade against the protocol itself – and token holders have certainty about the economic value of these transactions. Balancer allows us to customize various economic parameters of the pool, tweaking the amount of liquidity it provides. For example:

Pool Assets. Balancer lets you hold up to 8 assets in the pool. In our example, we just have TKN and ETH. But if your network supports multiple payment tokens (e.g. ETH plus a variety of stablecoins), you can add or remove liquidity of TKN with other tokens simply by changing the index index. For example, you could make the pool 80% TKN, 10% ETH, and 10% Dai, and deposit either form of income into the pool. This also means you can make TKN liquid against more than one pair.

Pool Index. Balancer’s key innovation is its ability to maintain a set index. In our examples, this is what allows us to create a pool that’s 80-90% TKN and 10-20% currency tokens. But you can easily change the proportion to any weight. What this will affect is the overall liquidity of TKN in the pool. Generally, a higher proportion of TKN will increase its slippage, which makes trading against the pool more expensive by increasing the sensitivity of the price of TKN to changes in its supply and demand.

Exchange Fees. We can set our pool to charge trading fees of up to 10%, to the benefit of the treasury. This allows us to program the premium to market at which tokens are bought or sold. Changing the trading fees makes the Treasury Pool more or less competitive in the market. If you want to discourage buyers in order to protect the network’s TKN balance, you go for a higher fee.

These parameters can be set and fixed forever, programmed via smart contracts, or updated via a DAO vote depending on each network’s requirements. In essence, you can program how much liquidity the network provides to the market. The more liquidity you want to create, the cheaper you’ll want to make trading against the pool – such as by increasing the proportion of currency tokens to reduce slippage, and by lowering trading fees. If you want the network to be the liquidity provider of last resort – the last place people go to buy and sell TKN – then you increase trading fees and slippage.

The ability to change these settings via a DAO allows a network to affect the economics of its token in response to market conditions simply by voting on changes to these Balancer settings. For example, in a bull market, it might make sense to increase the balance of TKN reserves in the pool along with the trading fees in order to accumulate more TKN for the treasury. In a bear market, TKN liquidity might be more important for network health – then, lowering the cost of exchange would be more useful. This is not too different from what central banks do to manage economic cycles.

Bonus: Similar to the automatic buyback and capitalization functions, our Smart Treasury can also be very useful in liquidating stakes or collateral in the network. Here again, protocols like MakerDAO rely on keeper bots and incentives to manage liquidations, but whereas using a Balancer pool provides the equivalent functionality for free.

All in, this is where the “make” in buyback-and-make comes from. Instead of wasting tokens by burning, now we have something very interesting happening. On one side, TKN is being withdrawn from the Smart Treasury by the Protocol as incentive tokens are issued. On the other side, any excess income landing in the pool as network usage increases is automatically used to automatically buy-back TKN and refill the pool. Instead of burning bought-back tokens, they become available for re-issuance following the same incentive model. Buyback-and-make is not destructive to the market cap the way burning can so easily be. And as a bonus, the many features Balancer provides drastically simplifies code, protocol and mechanism design.

But my favorite feature of this model is that it allows us to create permanent incentive models with continuous issuance while also keeping a maximum supply of tokens. During the bootstrapping phase of our network, there might be more TKN leaving the pool than entering from buybacks. But as the network matures, a balance is found between inflows and outflows of TKN. By recycling bought-back tokens into constant rewards and liquidity, we ensure there is always an incentive to continuously capitalize the system. This is great because it allows the network to leverage the benefits of issuance forever, while keeping the economic benefits of buybacks and the certainty of a known maximum token supply.